By: Reid Griffin, Contributing Writer

Only a single lifespan separates the ratification of the 19th Amendment—permitting one-half of the United States’ population to vote—from today’s presidential election season; and grandparents of Saint Leo University students are old enough to remember the ratification of the 24th Amendment, finally prohibiting the use of poll taxes.

The battle is far from over. Now that efforts to limit voting rights have failed, opponents of a free and fair democracy turn to voter intimidation.

The Election Protection Coalition defines “voter intimidation” as intimidation to influence an individual’s participation in the electoral process. The following are all examples of voter intimidation: misinformation, imitation, intrusive questions, and other harassment. Misinformation about candidates and voter requirements, imitating an election official, questioning voters about their background or ballot choices, and aggression towards voters of different demographics can all be a form of voter intimidation.

This means that demanding someone to disclose whom they voted for, loitering around poll centers, and claiming that voters must speak English are all forms of voter intimidation. These actions intend to limit someone’s willingness to vote.

Whether or not the attempt is successful, voter intimidation is a federal crime punishable by a fine or imprisonment.

With the progression of the 2020 U.S. election, incidents of voter fraud, intimidation, and suppression occurred. The Better Business Bureau reported an increased number of scammers using the election season as a smokescreen for scam calls. The Washington Post reported a California drop box and a Boston drop box set on fire. Snopes confirmed Californian Republicans illegally set up their own drop boxes. On social media, rumors circulated that anyone can show up to the polls as a vigilante “watcher.”

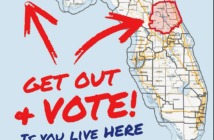

Groups of unauthorized individuals hanging around polling centers are a clear example of voter intimidation. According to the National Association of Secretaries of State website, polling centers in Florida may have a limited number of poll monitors per poll center—typically one monitor for each side of an issue, party affiliation, or candidate. The monitors can challenge the right of a person to vote. While some people are under the impression that a poll watcher can be anyone who wants to watch over a polling center, no one else is permitted to challenge a voter; doing so without proper qualifications is harassment.

Dr. Frank Orlando, an instructor of political science at Saint Leo University, struggles to remain optimistic as the political battleground moves onto social media platforms.

“Misinformation has always been around. We know this,” he said, “But it’s never had the ability to spread as quickly as it has now.”

Orlando believes that one of the major problems is that voters, having made up their minds about political issues, may not want to avoid misinformation. Social media is designed to hijack the brain’s dopamine system, making the entire system a treacherous place to be educated. Any information, true or false, that supports their existing views will be consumed without question.

“How do you break out of that?” Orlando asked. “It’s hard.”

There is no easy answer to the complex, ongoing issue. Orlando offered some suggestions—healthy skepticism, following people of differing views, and finding reputable sources—but at the end of the day, there is one unsatisfactory conclusion: voters can protect themselves from misinformation by learning to be better citizens.