By Caitlyn McGregor, Staff Writer

The history of U.S. presidential elections, from the early years to the present, illustrates how campaigning has evolved, particularly in terms of negativity and personal attacks. In 1788, during George Washington’s first election, there were no political parties, so the campaign process was much different compared to today’s highly organized political landscape. They labeled Washington as a national hero, and his election was seen as a consensus victory rather than a competitive race.

However, things began to change with the rise of political parties like the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. By 1800, the election process had become much more contentious, with personal attacks and propaganda taking center stage, despite Washington’s warning against partisan fighting in his farewell address. According to the Philadelphia Church of God, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams had once been best friends, but became bitter rivals due to the election. This division deepened after Thomas Paine’s book, The Rights of Man, gained popularity in Europe. Jefferson urged American printers to distribute it, leading Adams to be ridiculed and labeled a “monarchist,” while Jefferson was accused of supporting hereditary monarchy.

As the 19th century progressed, campaigns grew increasingly cutthroat. Newspaper, the primary news source at the time, often published stories aimed at rousing suspicion about the candidates’ moral character. According to Britannica, the 1828 election between Andrew Jackson and John Quincey Adams is one of the most famous and memorable in American history. Both candidates made harsh allegations against one another: Jackson’s supporters accused Adams of elitism, while Adams’ labeled Jackson a thug and a murderer. The election became a spectacle, where emotions and hostility played a key role in galvanizing voters.

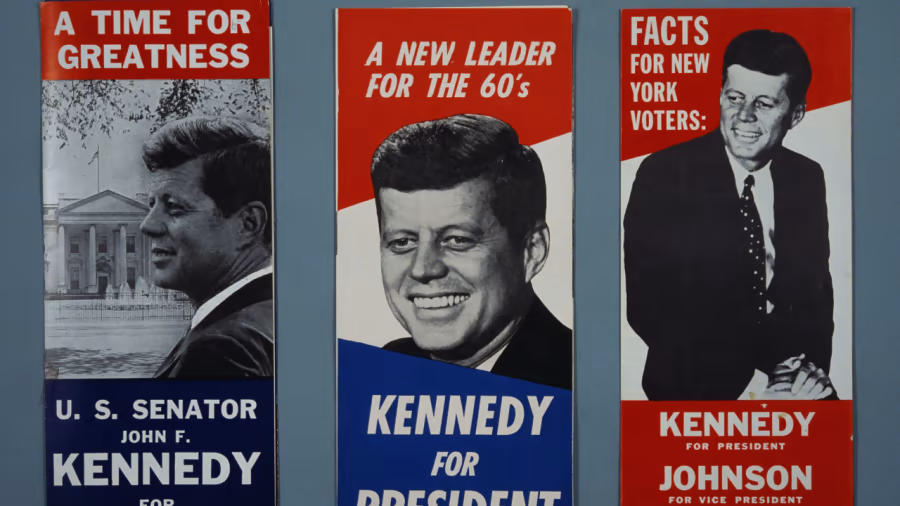

It didn’t stop there, either. This trend continued into the 20th century, with the rise of mass media—first radio, then television. The 1960 Kennedy-Nixon debates marked a turning point, when how candidates looked and acted on screen became just as important as their policies. As political views grew more polarized, negative campaigning became a favored tactic to rally supporters and attack opponents, often overshadowing substantive debate.

In the 21st century, elections have been dominated by negativity: attack ads and social media campaigns spread divisive messages faster than ever before. Negative campaigning is certainly not new, but the way technology has changed the game has raised the emotional stakes of today’s politics, making the political landscape one of high-intensity rivalry. This shift reflects broader societal changes, such as the influence of media on public opinion and growing voter polarization, which have reshaped the way Americans view and engage with politics.

It is striking to think about how different this is from the very first elections. What was once about consensus has turned into a battle of personalities and emotions. It makes one wonder what campaigning will be like in the future!