By Sophia Sullivan, Contributing Writer

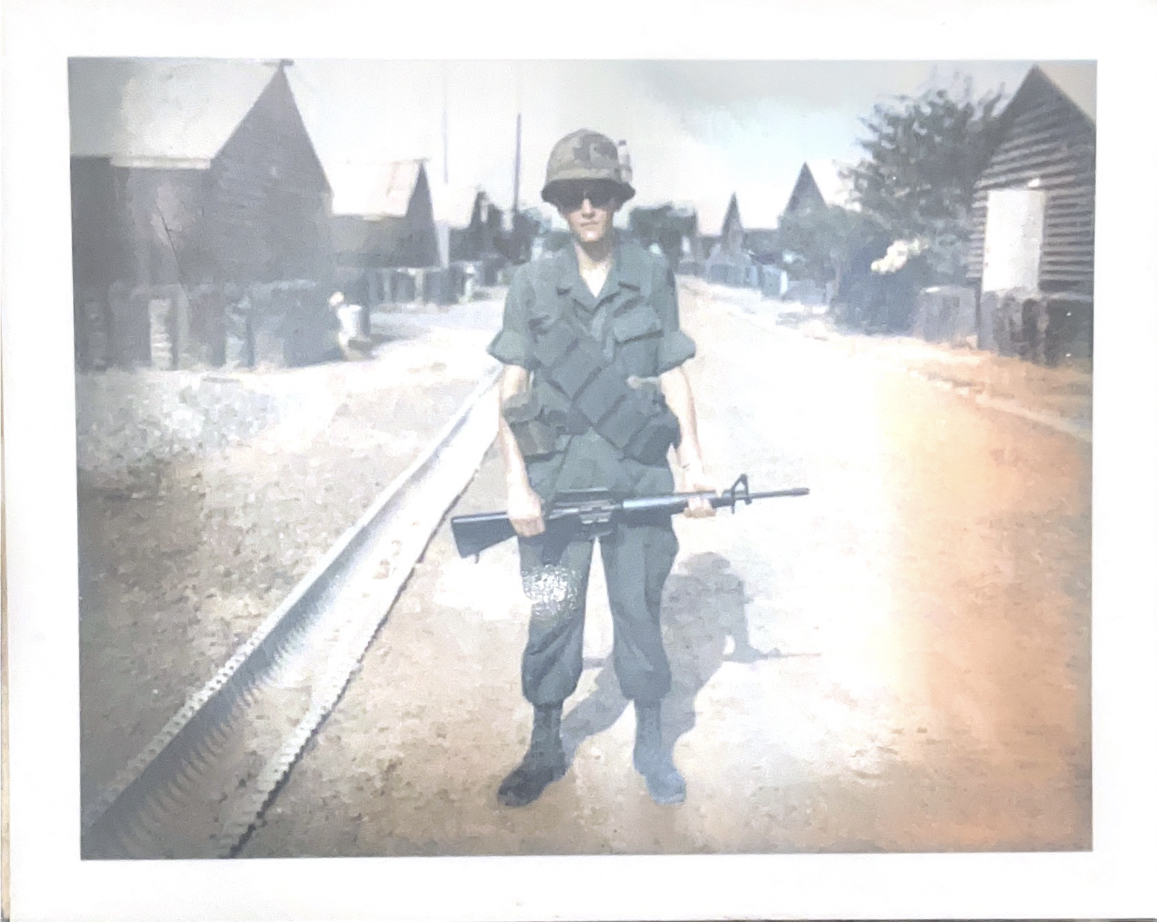

Imagine marching through jungles for months, unaware of what’s on the other side, and unable to remove your boots for fear of swelling. This was a reality for Donald Popp, formally a Specialist Fourth Class in the United States Army.

Popp grew up in Gary, Indiana with his father, mother, and three sisters. He attended Lew Wallace High School, where he first laid eyes upon his future fiancée, Cynthia Railing. Although he wasn’t too interested in academics, Popp proved himself in other ways. He was always fascinated by auto mechanics and worked as a body shop apprentice after graduation.

In 1969, Popp received his draft at the age of eighteen. Because he was aware of the conflict in Vietnam, he was expecting to be conscripted. He was then sent to Missouri for eight weeks of bootcamp.

“Bootcamp was trying. And I learned a lot,” said Popp. Even in the face of the uncertain situation, Popp showed his willingness to better himself.

When his group arrived in Vietnam after bootcamp, they were greeted with a bombing. They hadn’t even received their weapons yet, so the men were instructed to enter the bunkers until it was safe to come out. Afterward, the men were sent to tents and given their companies and job classifications.

“While I was there, they had flatbed semi-trucks full of wooden coffins, and I asked what those were, and a sergeant said, ‘You’re their replacements,’” recalled Popp.

It was a sobering thought for Popp, who would spend the next eleven months involved in the gruesome combat of Vietnam.

Shortly after his arrival, Popp was placed in the First Infantry Division and travelled right next to the Cambodian border. They were the first company to enter Cambodia, where they were ordered to confiscate weapons, bicycles, and anything that the Viet Cong could use against the South Vietnamese and Americans.

During his time in Vietnam, Popp was seriously injured once. However, the injury left a lifelong remembrance.

“From weapons—that’s how I injured my ear. I couldn’t hear nothing out of my left ear. It was like a seashell,” said Popp. “The medic took a piece of cigarette paper and wet it and took tweezers and put it way up on my eardrum to fuse the hole.”

He never heard out of his ear the same way again. Popp also experienced jungle rot around his waist as a result of wading through rice paddies. Additionally, Agent Orange caused lasting effects for Popp, such as diabetes and a thyroid problem.

Despite these trials, Popp also remembers the better parts of his time in Vietnam, like bringing children candy in an orphanage, joining a softball league where he won the championship for his company, and visiting Saigon, where he called his fiancée.

“That’s the only time I could ever call her,” he reminisced with a wistful grin upon his features. Clearly, the thought of his love back home allowed him to continue fighting.

One night when Popp was on patrol, his dog began to act differently, and he saw something moving in the tall jungle grass. Popp shot into the brush without permission and discovered he had shot a young Viet Cong boy laden with grenades.

“His job,” Popp said, “was to blow up our platoon.”

He was immediately sent home with two Bronze Stars in hand for heroic achievement and selflessness for risking his life for the sake of his platoon. He seemed proud of his heroism, but a grave look remained as he remembered that day.

In March of 1971, he headed for the United States and landed in California. In the airport, the crowds harassed the soldiers, calling them “baby killers” and spitting on them. Like many Vietnam veterans, Popp experienced difficulty reacclimating to “normal” life.

“It took me a year at least, maybe even longer,” Popp explained.

The fact that Popp knew he fought for this country and everyone’s freedom brought him a sense of comfort, but he was concerned what society would think of him for being involved in the war.

“Knowing that my life would change helped me cope,” said Popp.

After eleven months of solely communicating by letters, he finally reunited with his true love. Popp promptly returned to Indiana and married his fiancée on November 6, 1971. The couple eventually had two daughters, and five grandchildren.

Popp also returned to work six months after coming back from Vietnam. He began at a Chrysler dealership and worked at many other body shops before retiring from a successful career as a body shop manager.

Nearly a half a century after the war, Popp and one of his daughters partook in the Honor Flight, where he and other Vietnam veterans were given an exclusive tour of Washington D.C.

“It was one of the best days of my life,” recalled Popp. “People in the airport were clapping at us, and it was the welcome I never got when I landed in California.”

The veterans were whisked around the city as traffic stopped for them, were shown monument after monument, and enjoyed a first-class flight.

“They treated us like kings,” Popp remarked.

While at the Vietnam Wall, Popp found the name of one of his close friends from his platoon whom he placed in a body bag on one of their last sweeps. That friend had let Popp borrow his camera while they were serving in Vietnam.

“That’s something I’ll never forget, and I still got his camera,” he said.

Popp’s experience in Vietnam shaped him into the person he is today. While many Vietnam veterans turned to drugs, mental illness, or suicide, Popp turned to his wife, daughters, and eventually his grandchildren for support. He took his horrendous circumstances and used them to become something so much more. And that is what the Vietnam War taught this country: that even in the face of uncertain times, it is vital that we support our soldiers.